Textile making has a long history in Georgia, reflected in the diversity of different handicraft techniques, abundance of designs and wide range of typical imagery.

Being a common occupation for household women, young girls started mastering their handicrafts skills from the very childhood by processing wool, linen, hemp or silk for their dowry textiles. Marital function often determined the content behind the textile motifs, which in turn seem to relate to the ancient cult of fertility and hence, the idea of wealth and family well-being.

Local fairy tales and beliefs, as well as common imagery constantly reoccurring across different fields of folk art, allow us to put forward some suggestions on the possible symbolic content behind the imagery. Quite often, their roots can be traced back to the Bronze Age or earlier artifacts.

Amongst the common motives is the tree of life, which seems to be resonating with the archaic cult of fertility. In rugs and carpets, block printed blue tablecloths or embroideries, the tree is represented by a. a pattern generally known as boteh, or buta, called “mani” in Georgian, (due to the resemblance in the shape with the grapheme M of Georgia alphabet), which is a stylized motif of an evergreen cypress, b. a blooming tree, or c. a vine. As a symbol of eternal life, the pinecone being a fruit of evergreen also often appears with the same connotations in textile design.

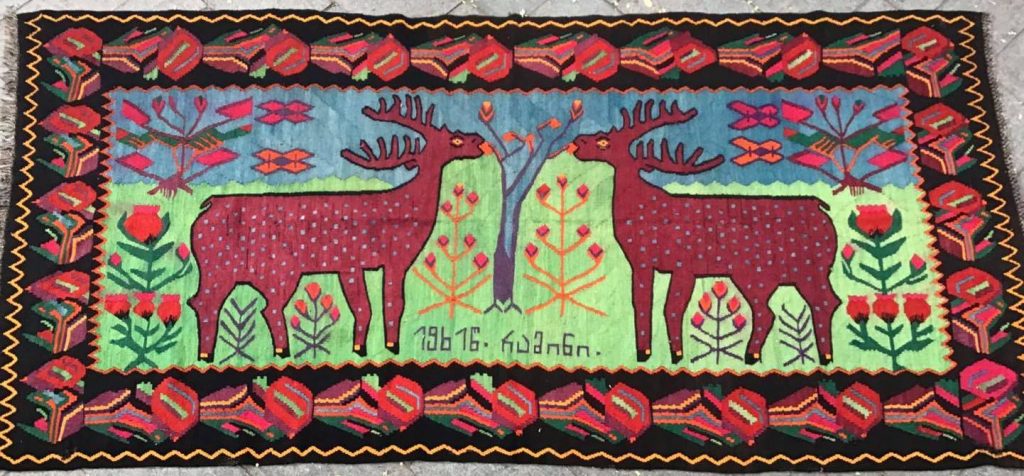

As an embodiment of the axis mundi, linking heaven, earth, and underworld, the tree of life is a universal symbol worldwide, however at same time it seems to be among the most widespread and deep-rooted local archetypes. Later in medieval period, due to its Christian symbolism vine tree became a counterpart of the “axis mundi”, while the motive of the birds or deer pecking its fruits became a representation of the soul of the Christian longing for salvation through Eucharist.

In textiles, the wide spreading branches of the tree of life are often replaced by a decorative rosette, which similarly to swirl, spiral, swastika, or concentric circle, is meant to be a symbol of a life-giving celestial body, the sun.

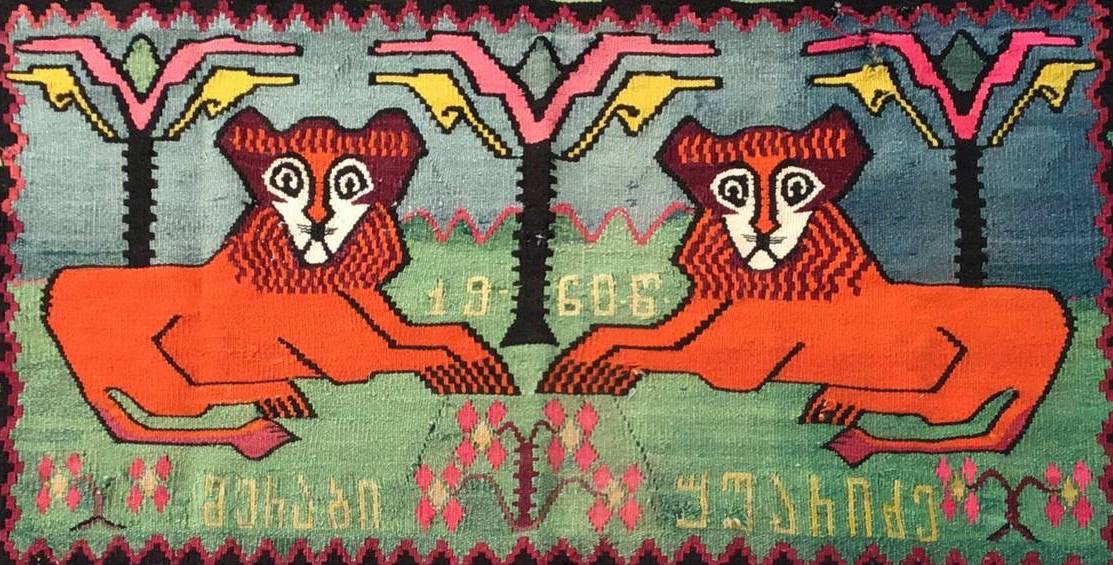

Another popular motive of Georgian textiles with the same solar symbolism is a lion, which often appears as a ferocious guardian of Garden of Eden chained to the tree of life. We come across this motif among the patterns of the blue tablecloth, which has a closest parallel in the famous stone-carved relief on the southern facade of the Ananuri church of the Virgin (1689 AD).

According to the folk beliefs, other zoomorphic images are also closely linked with the archetype of the tree of life: i.e., birds are supposed to reside on its top in the branches, whereas ungulates (deers, horses, etc.) live by the stem and fish, snakes, and other chthonic creatures inhabit the underworld nearby its roots.

The typical textile motives are birds, roosters, and peacocks, which are often found at in rug and carpet, blue tablecloths, and needlework designs (for example, the so-called “Daroshkas” typical to Adjarian region). Residing at the top of the tree the bird is considered as a mediator between this world and heaven. A peacock (similarly to a phoenix) that renews its feathers every spring is a symbol of rebirth and eternity, while the beauty of its spread tail is associated with the blossoming part of the axis mundi.

Amongst the abundance of zoomorphic motives, the stag/deer is perhaps the most popular archetype typical for textiles and generally, for many different fields of Georgian folk art and craft. The wide antlers of a stag act as the equivalent symbols to the blossoming branches of the tree of life, which bridges two different worlds: the “lower” and the “upper”. Deductions may be made from examples we have in local lore and fairy tales, where we come across the image of a stag holding firmament with its giant antlers. This archetype of the stag association with the celestial symbolism reoccurs in the 19th century in particular among the blue tablecloths pattern, where the body of this animal is marked with astral signs. The origins of this motive can be traced back to the ancient zoomorphic imagery on Bronze Age axes, belts and openwork buckles found among the archaeological artifacts on the territory of Georgia and south Caucasus.

As an aquatic creature, a fish is another symbol directly associated with the life-giving power of water and therefore with the idea of fertility and generative power. Later, as a symbol of Christ, it became a motif related with the Eucharist. Depiction of the fish images on the table accessories, and especially the motive of cross-marked fish found amongst the blue tablecloth patterns and silver tableware motives, makes the Christian connotation of this symbol even more exposed to the spectators.

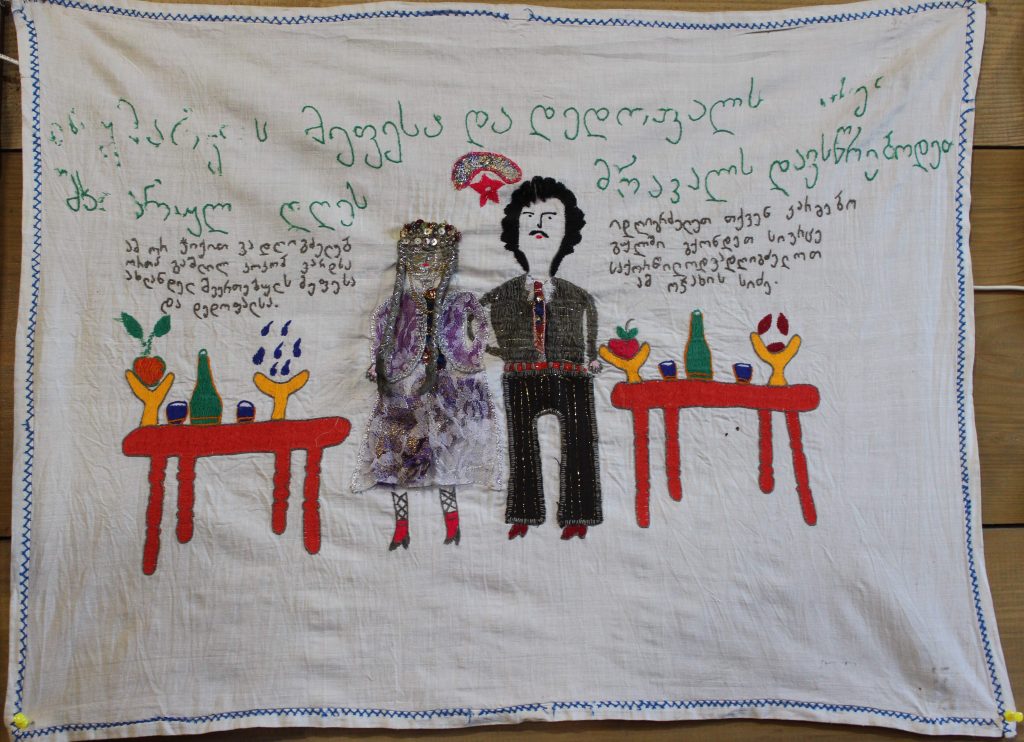

At the beginning of the 20th century, the integration of zoomorphic images in rug and carpet design was further stimulated by the spread of imported soap package ornaments with attached zoomorphic illustrations. The special popularity of the stag, lion and rooster images however, was most probably determined by their coincidence with indigenous traditions and visual archetypes accumulated in the collective multi-layered memory shaped throughout millennia. The integration and spreading of the Soviet symbols such as the five-pointed star, together with the hammer and sickle in the folk art, embroidery and especially in openwork wooden balcony patterns, could serve as another vivid example of the overlapping symbolism of images. A star being a celestial body, might fall in line with deep-rooted astral symbols, while a hammer and a sickle being agricultural tools, might resonate with the tradition of St. Basil’s ritual bread-men or fortune bread baking traditions, as part of the New Year celebration ceremonies. We know that among other zoomorphic figures, agricultural tool-shaped breads were baked to bring more luck, harvest and wealth to the families. If we bear in mind the particular background, the wide popularity and integration of the particular Soviet symbols in line with ancient archetypes is not to be wondered.

The constant recurrence of the typical zoomorphic imagery in the design of textiles and other fields of art and crafts i.e. woodcarving, openwork balconies, ceramic or silver tableware, gravestones decoration, etc., as well as the continues popularity of these images among self-taught artists and artisans until today, speaks to the livelihood of strong indigenous traditions and the multilayered unity of archetypal thinking deep rooted in the sub-consciousness of collective memory.

Author: Ana Shanshiashvili

The text is an adapted version of a lecture made in the framework of the online program “What Is Textile Telling Us?”. The program is implemented by the State Silk Museum through a grant from CEC ArtsLink’s Art Prospect program.