What is textile telling us? Through this seemingly easy question, we can talk about eras, different cultures, personal memories, and a society’s formation. Needless to say, textile has a special place in the collection of the Silk Museum. I present various practices of narrating through fabrics by discussing specific objects kept at the Museum and by making parallels with contemporary art. “Textile stories” also make a certain kaleidoscope of time, where the personal approach becomes an important part of collective memory.

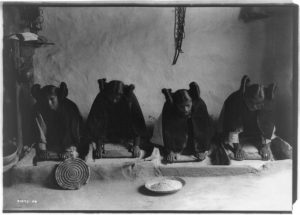

The history of the Silk Museum starts with the establishment of the Caucasian Sericulture Station. The station’s founder Nikolay Shavrov and its first employees participated in regional expeditions. They collected various artisan textiles for the museum, which among other materials show us the weaving traditions of the Caucasus. The Caucasian jejims, weaved towards the end of the 19th century, have a special place among them. Jejim is one of the types of carpet weaving that used to be made mostly in eastern Dagestan, Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan. Weaved by combining silk (warp) and wool (weft), it was also functional. Among the designs of the jejims, we find simple stripes, as well as geometric shapes and stylized forms. It is interesting that such motifs come from a collective view and present an ornament’s universal character.

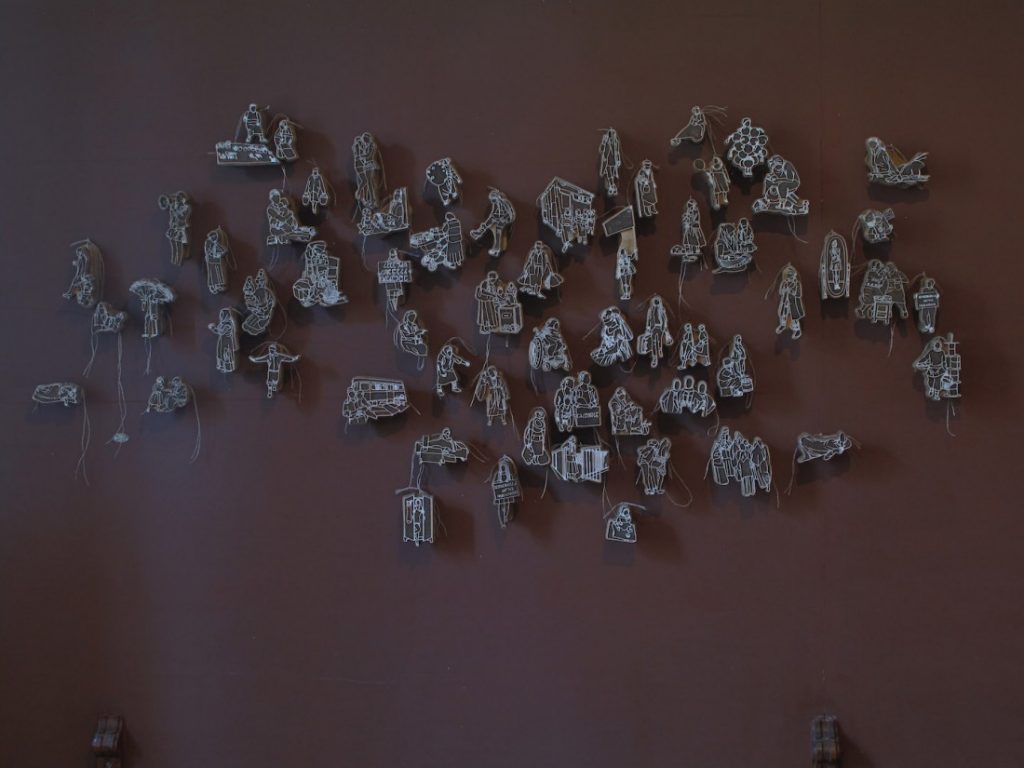

Various traditional techniques are used to get textile patterns. The traditional methods of working on textiles, or an ornament that naturally developed in daily life, often transfer into today’s world as a contentless design. “The Book of Patterns” – artwork by Tamar Chabashvili that was exhibited at the Silk Museum in 2016 – rethinks the traditional printing technology concerning the blue tablecloth and provides a conceptual approach of narrating through textile. The artist created block printing stamps based on the images of contemporary social life that are available on the internet. Instead of the traditional ornaments of the blue tablecloth, the work focuses on individual stories. The social perspective of “The Book of Patterns” derives from daily life and depicts the women around us, their psychological and emotional conditions, and social issues. Focusing on these, Tamar Chabashvili created a tactile book, wherein the intimate closeness of perception makes us think about those invisible layers, which are an indivisible part of the collective coexistence.

The museum’s lace collection from the 19th century “tells” us about a weaver woman, her family business for generations, and their forced migration. Together with their high aesthetic value, the laces as artifacts make us think about historical memory and painful experiences. Using the Leavers machine, these samples of laces were created in a company founded by a Jewish weaver Rosa Klauber in Munich, Germany. Because of the Nazi persecution, her descendants were forced to migrate to the USA. Klaubers reestablished lace production there and to this day their family continues the work started by Rosa Klauber.

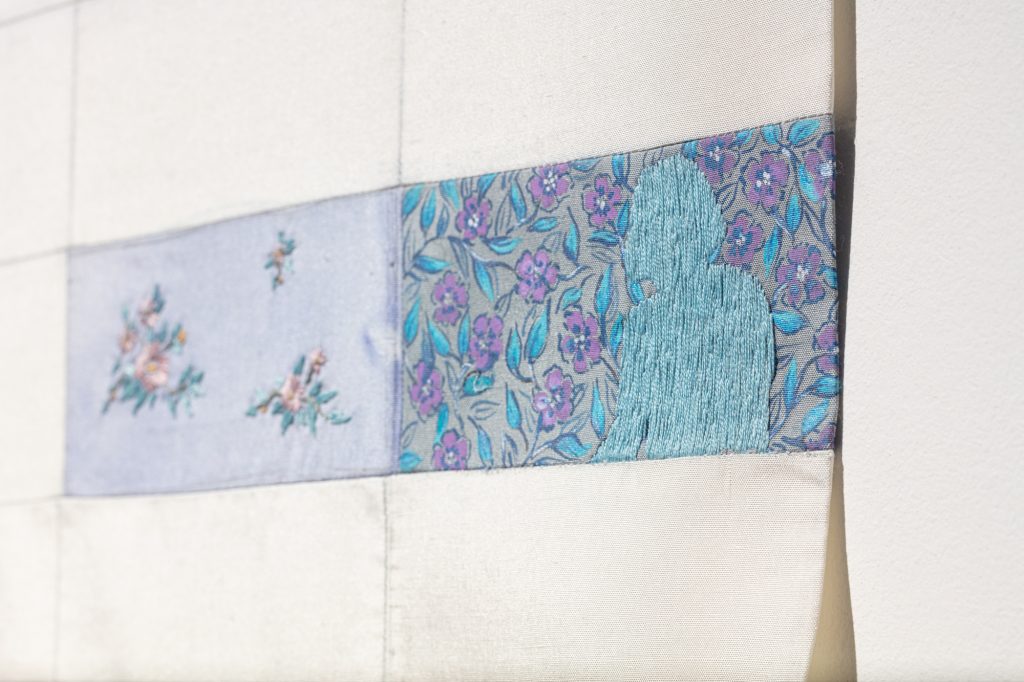

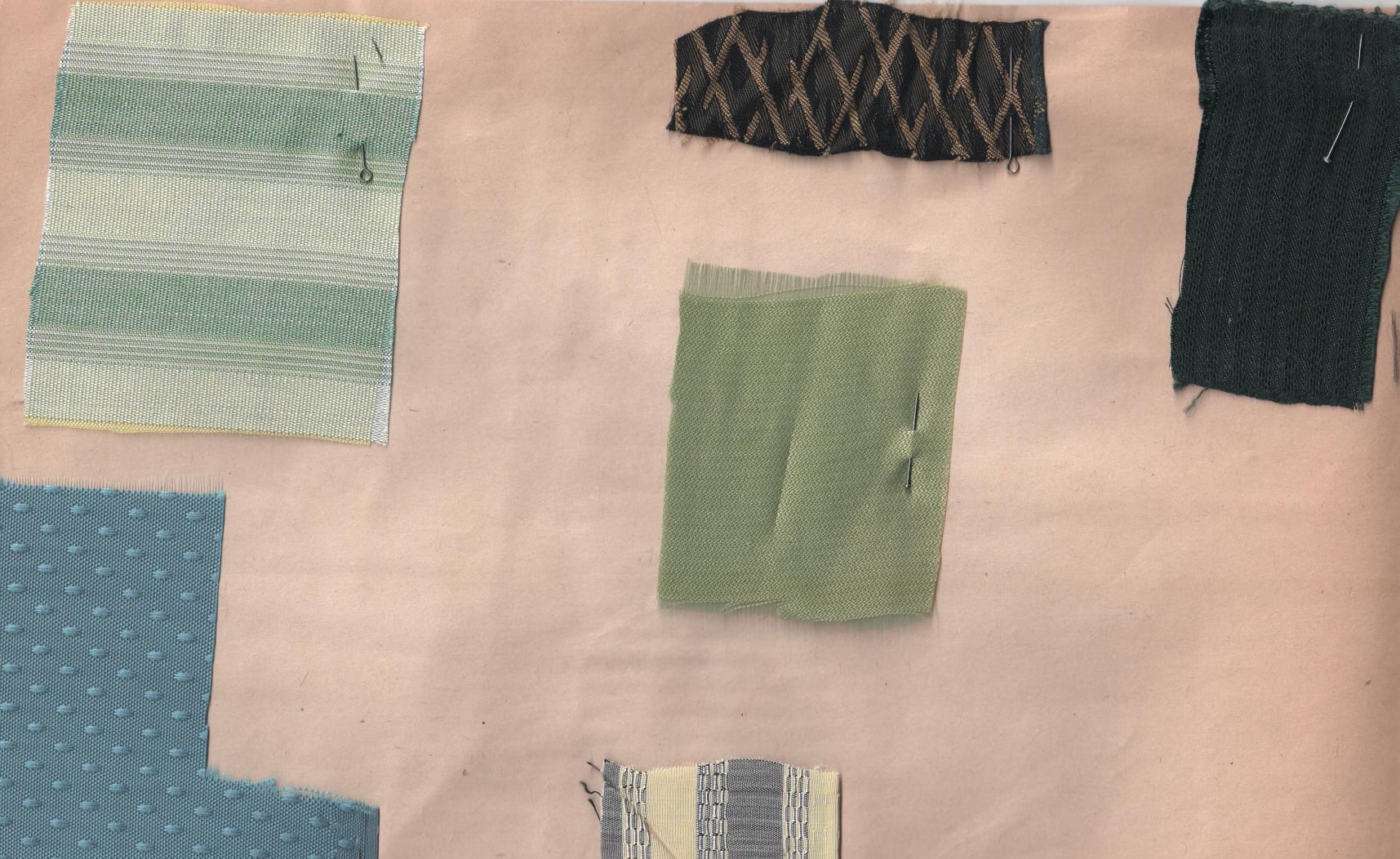

“A Long, Unending Road” is a work by textile artist Nino Zirakashvili that “speaks” about female labor migration. The artist researched personal stories of migrant women who left Georgia for work. Being in dialogue with them, Nino Zirakashvili transformed her empathy into the visual of her detailed, subtle work. During the research of personal stories, Nino Zirakashvili also observed the migrant women’s clothes. Through the quilting technique, she subtly developed various patterns that were inspired by the designs of industrial textiles (she also researched the Soviet-time textiles stored at the Silk Museum). With this work, Nino Zirakashvili dedicates a kind of an unending ode to those women, who work in the hardest conditions, take responsibility to support their families and often, have to refuse their personal wishes.

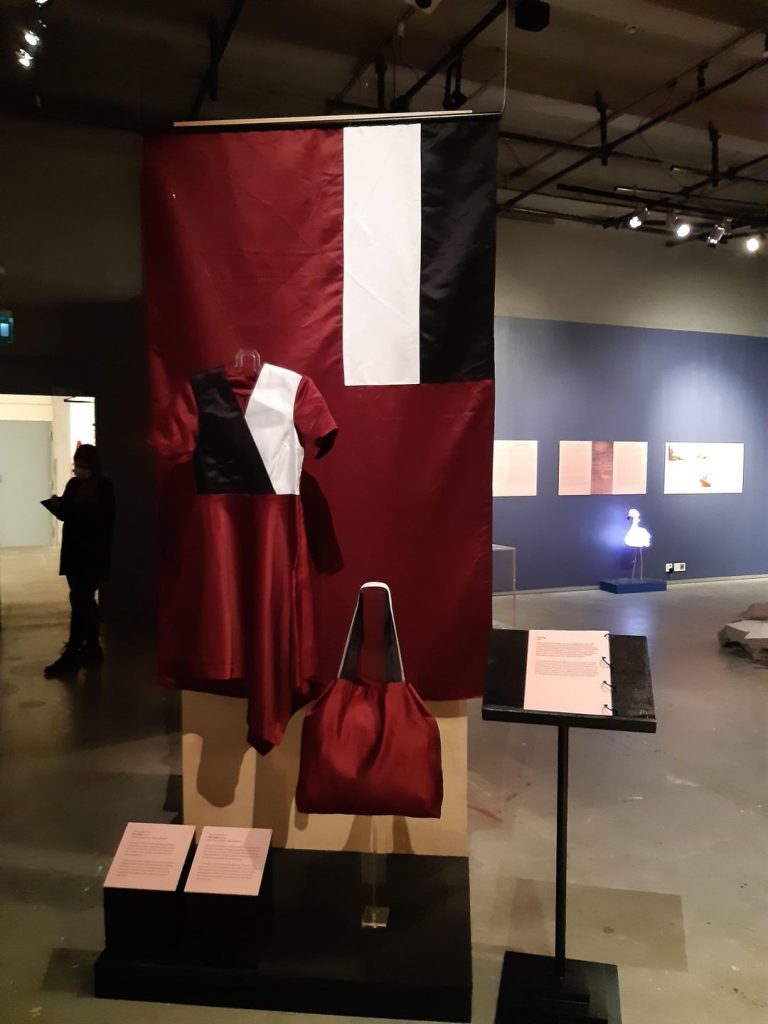

Thoma Sukhashvili and Maia Sukhashvili’s joint work “Tailor” is a direct and intense transformation of a personal story into a collective history. The installation is currently exhibited at The Finnish Labour Museum Werstas (Tampere). By showing the story of one woman, it tells us about the chaotic, hard reality of Georgia in the 90s. With the passing of time, Thoma Sukhashvili presents his family story and his mother’s handmade objects in a new context. The work shows how the flag, the independent country’s national symbol transforms into a functional dress, and afterward – into a bag. The tailor (Maia Sukhashvili) used this bag to take the products to the market, in order to support her family. In this case, the textile is not an art object in itself, but a real artifact. Presented in the context of an installation, it makes us critically think about the difficulties of living in Georgia in the 90s.

As a network of collective memory, through textile stories, we can discuss personal narratives that coexist in socio-political contexts. During the Silk Museum’s online workshop – “What Is Textile Telling Us?” – these layers are discussed from different perspectives.

Author: Mariam Shergelashvili

The text is an adapted version of a lecture made in the framework of the online program “What Is Textile Telling Us?”. The program is implemented by the State Silk Museum through a grant from CEC ArtsLink’s Art Prospect program.

Pingback: itemprop="name">What is textile telling us about different eras, personal memories, and social transformation? - Cold War Childhoods