The State Silk Museum preserves a small, but a very valuable collection – cardboard boxes for silkworm seed (eggs) transportation. The story of this collection is directly related to the creation of the museum, back then a part of the Caucasian Sericulture Station. During the current pandemic and isolation, it’s interesting to remember certain aspects of the museum’s history and its collections.

About 150 years ago, Europe faced a silkworm disease called pebrin. The silk production was nearly destroyed and local silkworm species were close to extinction. The European scientific society began searching for the methods to fight the disease. Famous French scholar Louis Pasteur was the one solving the problem.

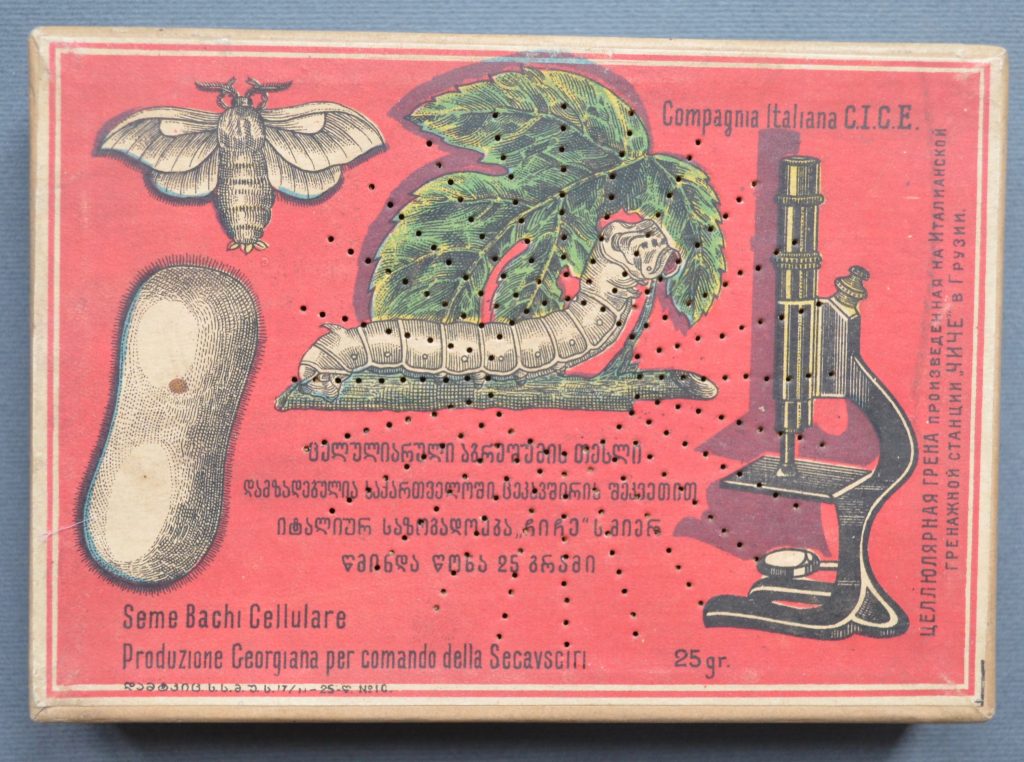

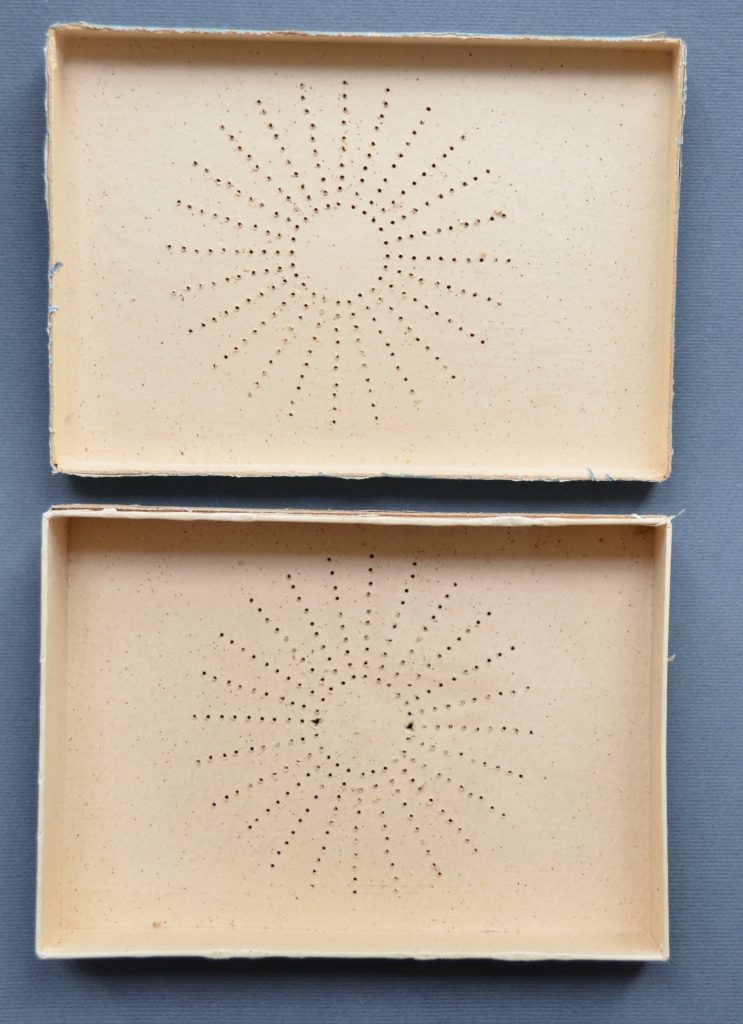

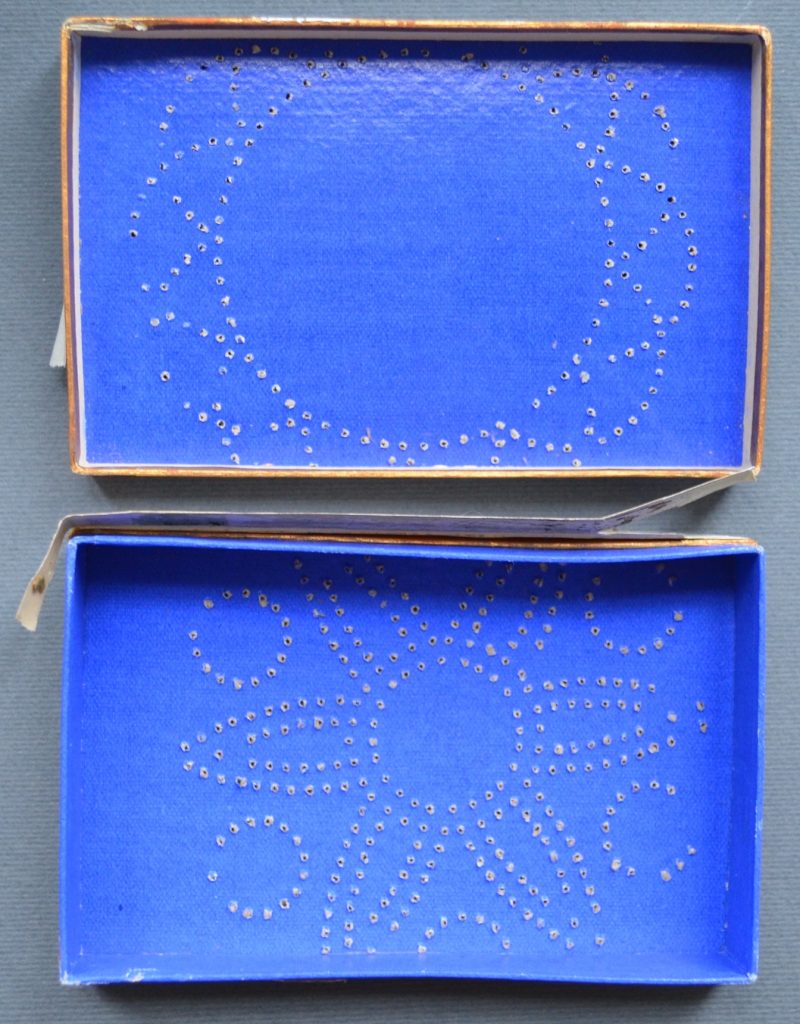

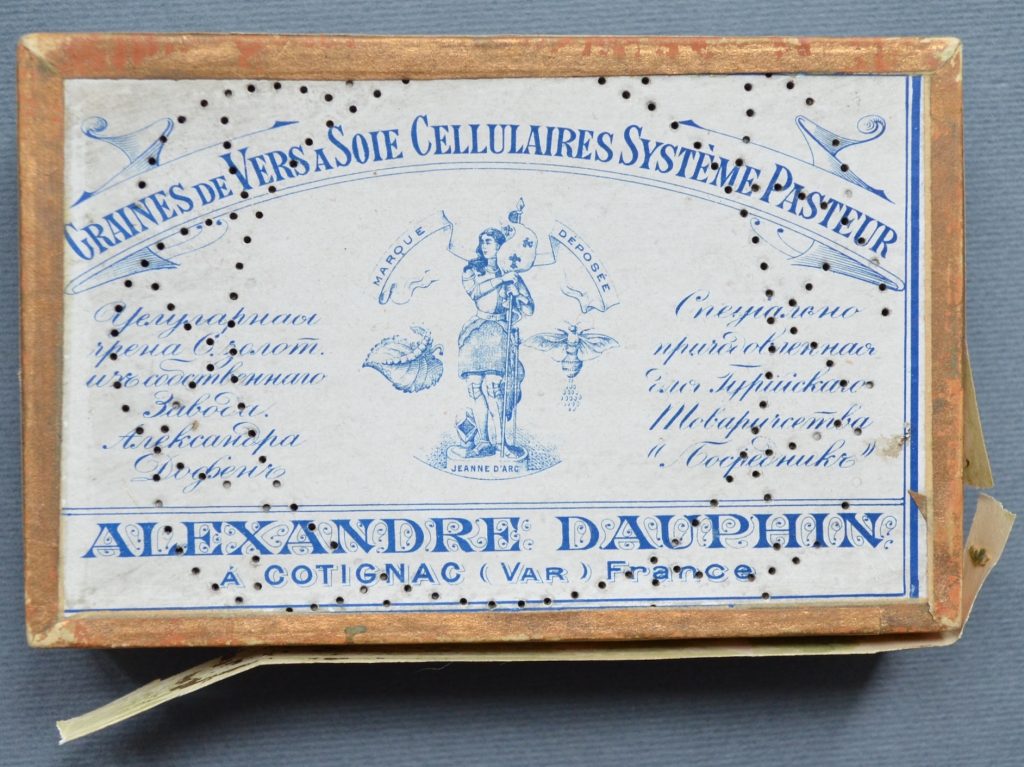

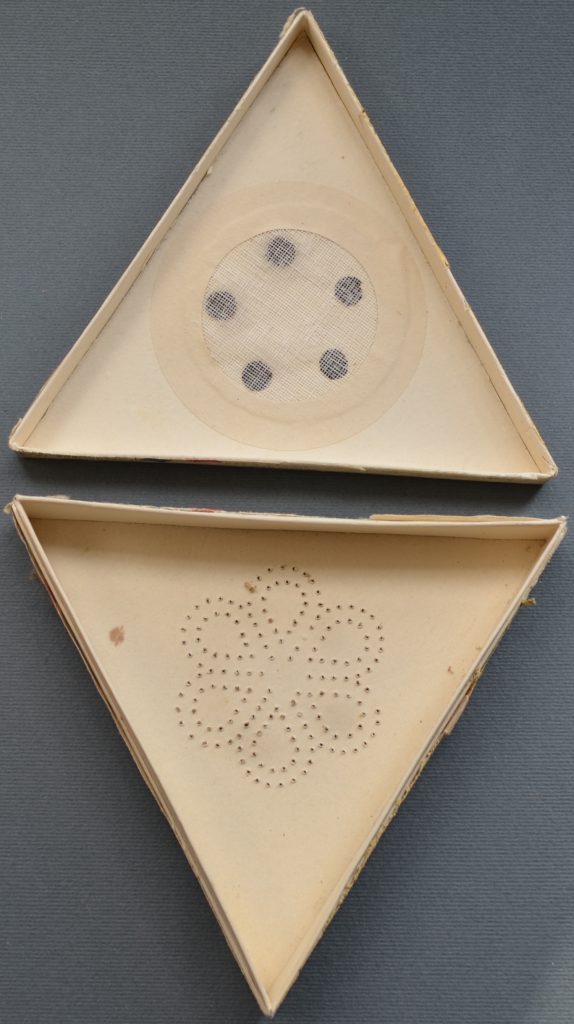

To prevent pebrin, Pasteur worked out a method known as “Cellular Selection” or “Pasteur Method”: each moth was put in a small breathable container called a cell and spawned eggs there.

Afterwards, the moth was undergoing double microscopic check: if it was immune to pebrin, its seed was also considered healthy and marked as “Pebrine free.”

This discovery led Pasteur to continue studying infectious diseases and he had great success in this field. Read more about his work and his role in immunisation on this link.

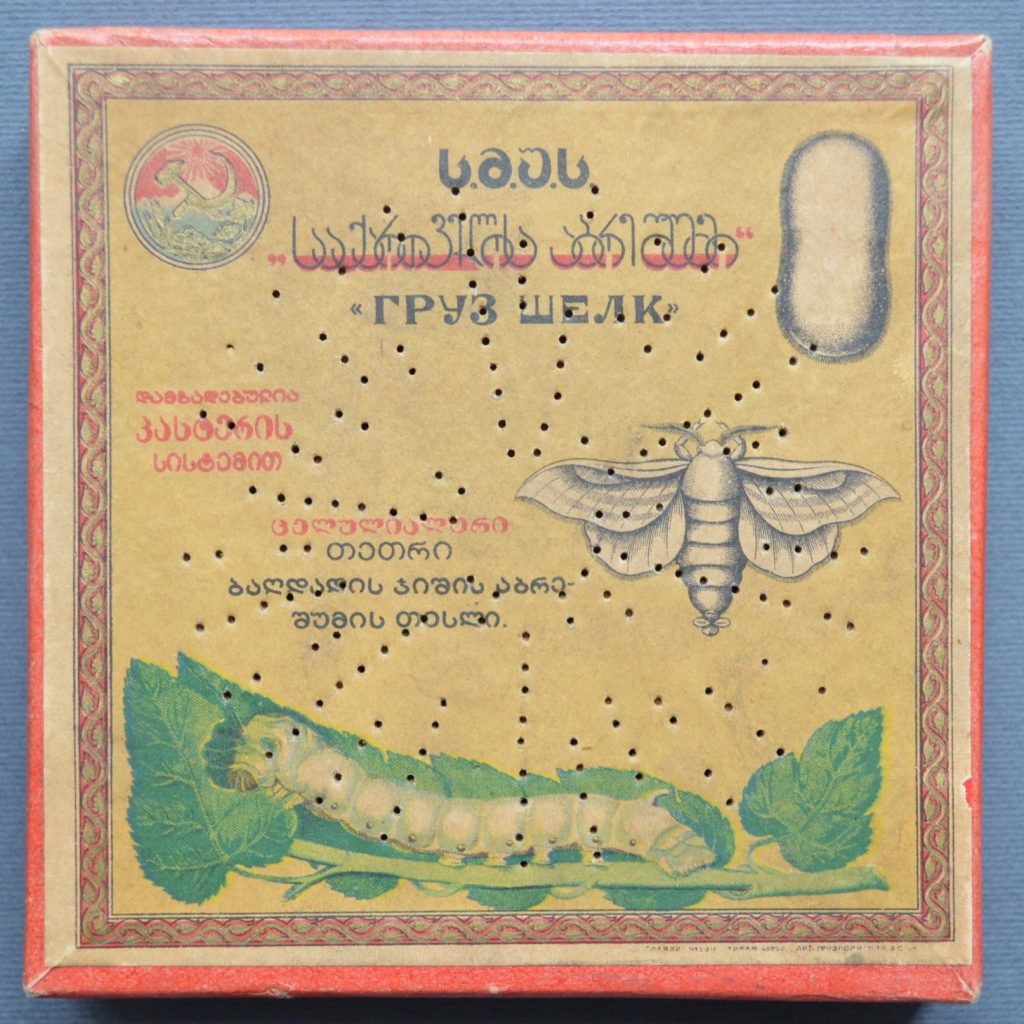

In 1870, the First International Sericulture Congress was held in Gorizia (then part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire). It resulted in spreading Pasteur’s incredible discovery around the world. Numerous establishments were created using the Pasteur system.

The most significant among them were the sericulture stations of Gorizia, Padua, the Caucasus and Tokyo.

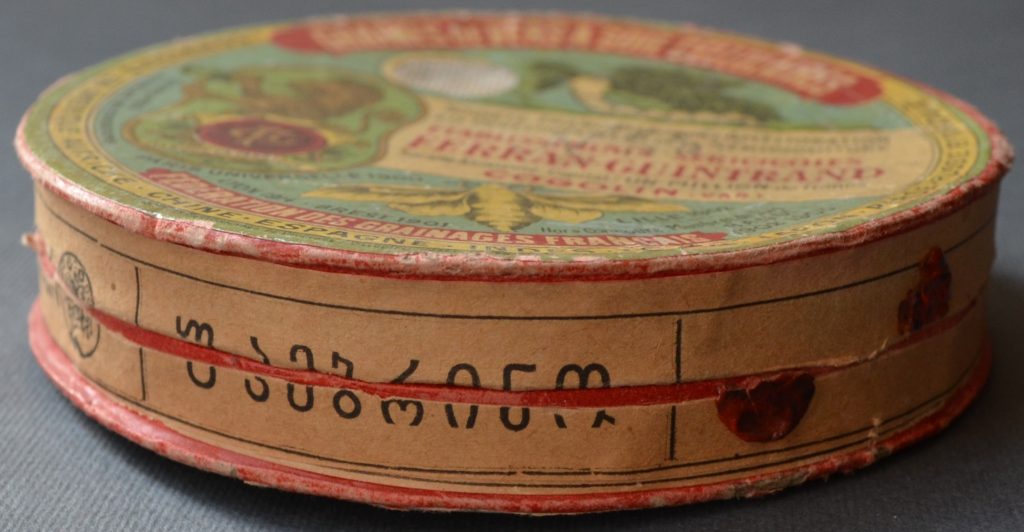

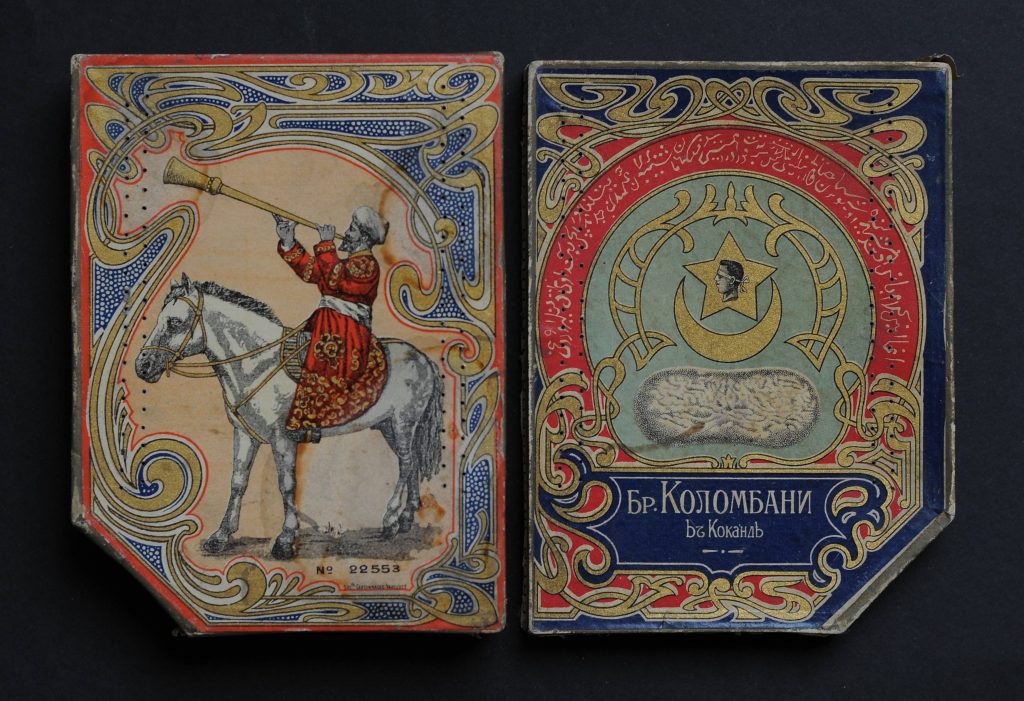

The Caucasian Sericulture Station in Tbilisi was founded by Noklay Shavrov. He travelled in Europe beforehand and was introduced to the Pasteur method in different stations and laboratories. The main occupation of the Tbilisi station was lab research and distribution of healthy seed among farmers. This particular process is illustrated on the cardboard boxes acquired by the museum from different countries.

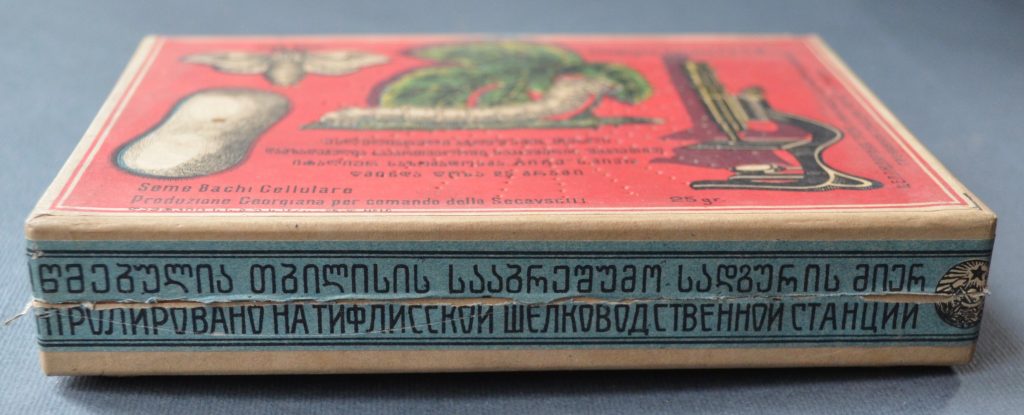

The boxes have texts in different languages, but the name of Pasteur is almost always present. These boxes also differ in their design – we see various shapes, images and emblems. One common detail is perforation, which provided oxygen to the eggs.

The seed received from different countries was tested and labeled as “Pebrine free”.

Over a century has passed and today these boxes can also be seen as metaphors. Besides their significant design, the containers in the museum’s historical vitrines tell a story of the defeated disease, collaboration and also economical and cultural connections among different countries.

Author: Salome Phachuashvili