During my internship in the Silk Museum dye collection was the first thing that I had to deal with. These few but various samples preserved in the glass tubes tell a lot of information about the history of the museum and sericulture in general and of course the natural history. This post briefly presents some of the collection pieces and the information preserved in the museum library.

The collection includes 97 different dyes, part of which was created at the museum laboratory while the others were acquired from different countries.

In his 1902 publication Vladimer Ivanov – the 2nd director of the Caucasian Sericulture Station – describes the process of dyeing as follows:

“Thread dyeing is preceded by the preparation stage called silk boiling. This process includes removal of the glue (sericin) from the thread. Although the sericin is relatively easy to remove, this process is quite complicated, because it requires for the fibroin (silk) thread to preserve all of its characteristics: firmness, elasticity, glitter, whiteness and softness. There are several methods of boiling that differ by duration and solution content, but in most cases a 72% Marseille soap and baking soda are used for it. As long as this process causes the silk to loose 30% of its weight and leads to the higher prices, there are some materials that are used to give the thread more weight. However, they reduce the quality of silk in case of overdose.”

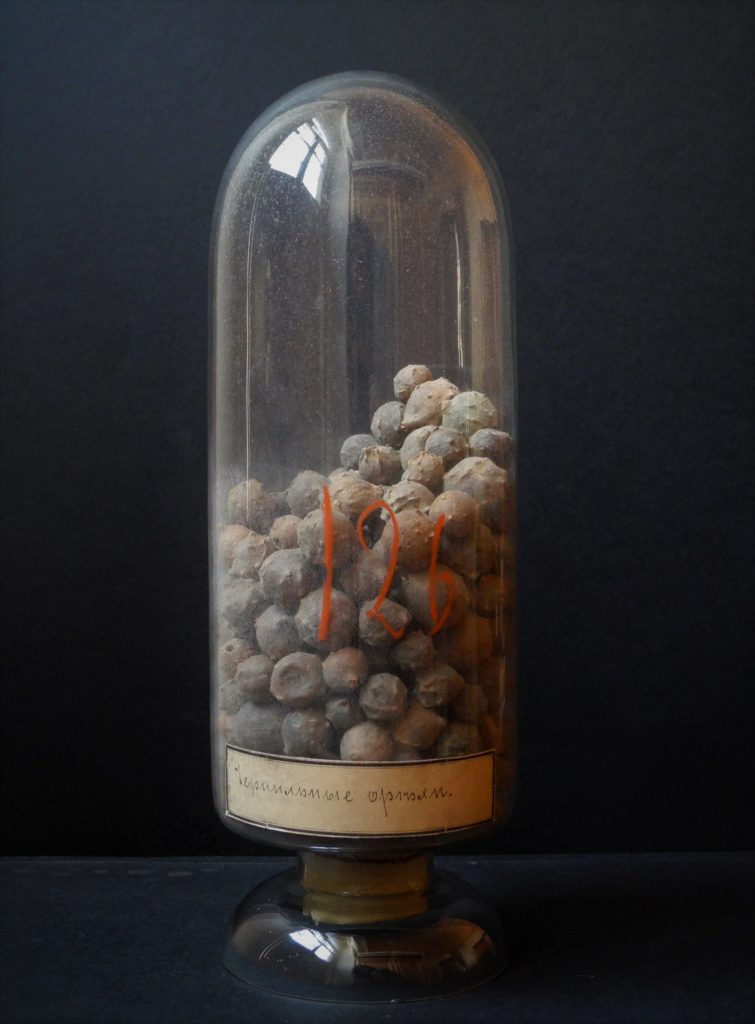

The museum collection preserves several substances used for gaining the weight:

Oak apples (a.k.a. oak galls; Lat. Galla (tumor plantarum) are produced as a result of gall wasp sitting on the oak leaf (the wasp larvae feed on the gall tissue resulting from their secretions, which modify the oak bud into the gall). The galls are used for the thread to gain weight and as a mordant. It is also used in medicine.

Cachou (a.k.a. catechu; Powder of Acacia catechu) is used for the thread to gain weight and as a mordant. It is also brown or green dye.

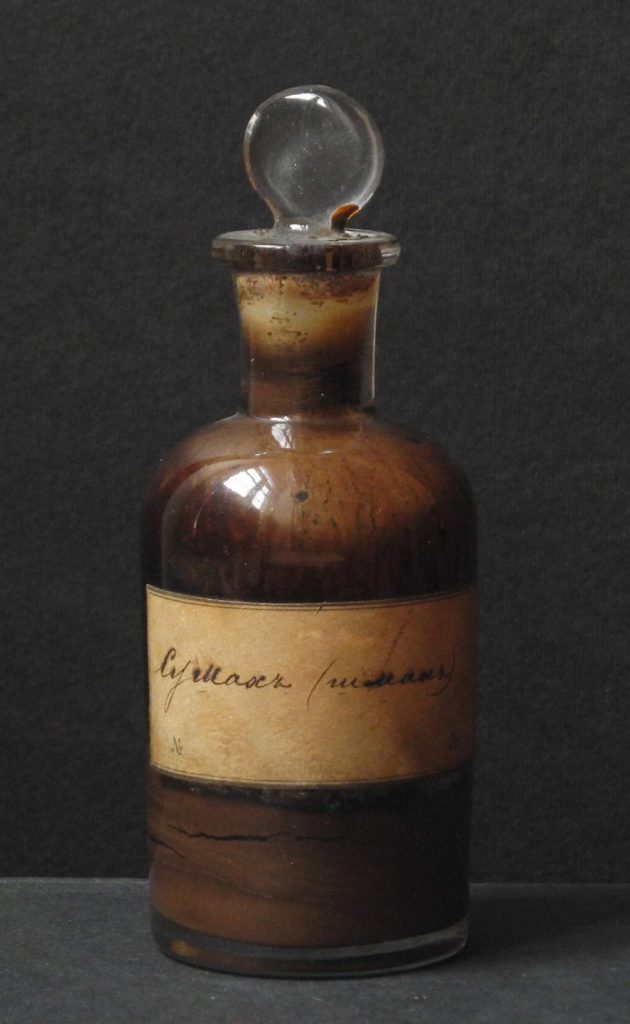

Sumac (Lat. Rhus corriaria) is used for the thread to gain weight and also for creating the souple silk. Sumac is part of the cashew family (Lat. Anacardiaceae) and usually grows in Africa and North America. The name derives from Latin and means “red”.

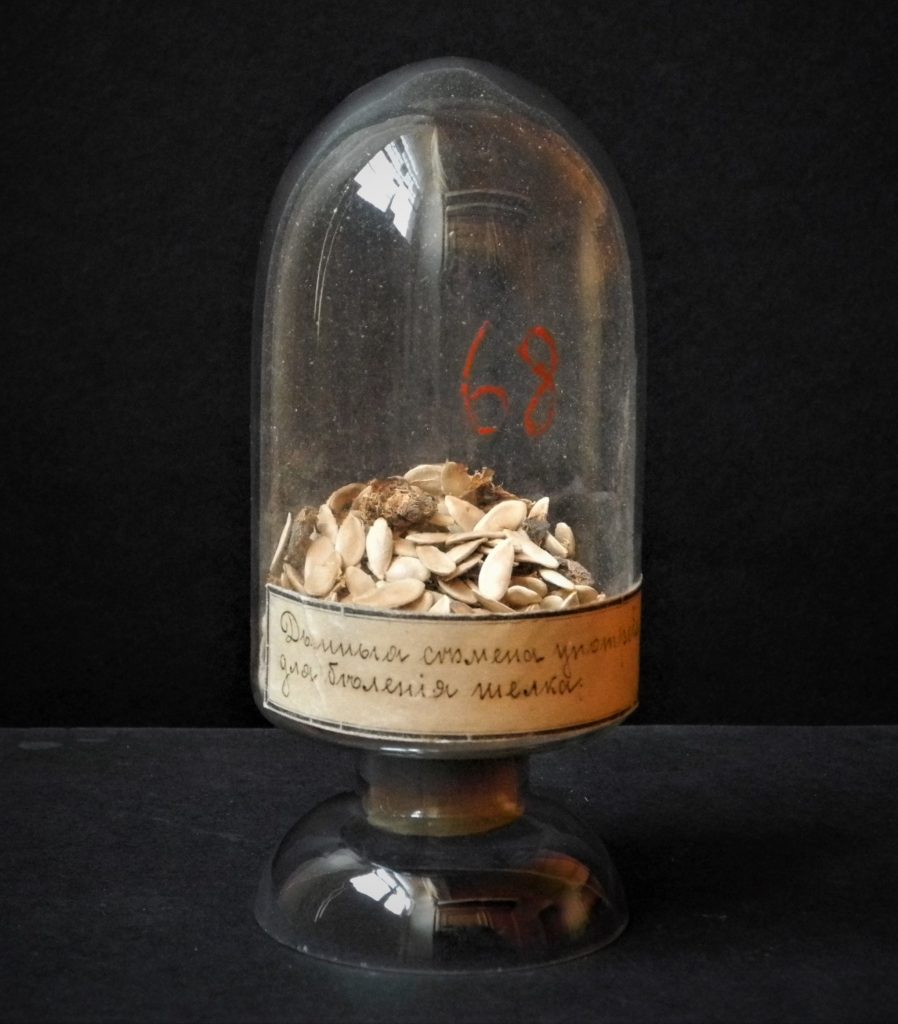

The boiling process is followed by whitening that was carried out with the help of melon seeds (Lat. Cucumis melo), also preserved in the museum collection.

“They put silk in the melon seed extract and afterwards wash and dry it carefully. In Kakheti they use ashes and soap for it. If the thread is not white enough, they smoke it with sulfur gas. For this purpose, they hang newly washed, damp silk on a stick and put it in a room where sulfur is lit. This process can take place in any nonresidential building, but a special camera is preferable.

All these procedures are followed by dyeing – boiling the silk together with the dyeing substance.”

The dyes preserved in the silk museum can be divided into two main groups: natural and chemical dyes. The first group includes herbal, animal and mineral dyes, while the second group is presented by aniline dyes.

Some of the outstanding herbal dyes include:

Mulberry tree leaves (Lat. Morus alba Folium) are commonly known as the primary food for silkworms. However, they also include dyeing substance, which gives the thread yellow color.

Safflower (Lat. Carthamus tinctorius) is one of the oldest dyes in human history. Its remains were found on the textiles from the 2nd millennium (12th dynasty) Egyptian tombs. It was also discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun. Safflower was one of the main yellow dyes until the aniline dyes were discovered in 1856. Nowadays it is used for other purposes: safflower oil is used in food and cosmetics. the flower is also used in medicine, as a substitute of insulin.

Logwood (a.k.a. blackwood, bloodwood tree, bluewood, campeachy tree, campeachy wood, campeche logwood, campeche wood, Jamaica wood; Lat. Haematoxylum campechianum) is spread in Mexico and Central America. It had a huge economic significance in the 17th-19th centuries, when it was exported to Europe as a dyeing substance. The Greek name of logwood is translated as “bloody tree”, as its wood is red from the inside, but changes its color when exposed to the air (firstly it becomes dark purple and then black). The dyeing substance is produced from the inner parts of the wood to get purple or black dye. It is also used to produce Chinese dark purple ink. The wood itself is used in furniture industry.

Roots of madder (Lat. Rubia iberica. Rubia tinctorum) – Around 55 species of madder is spread in the temperate climate of Asia and in the Mediterranean, some of them grow in the mid Europe and Africa, as well as in the South America and Mexico. Several species of madder can be found in Georgia. The dyer madder (Lat. Rubia tinctorum) has been cultivated since earlier times and it was used for dyeing silk, cotton and wool fabrics.The oldest piece of a textile dyed in madder was found in India, in Mohenjo-daro settlement ( 3rd millennium B.C.). Similar samples were discovered in the tomb of Tutankhamun as well as in Pompeii and Corinth. Madder is also used in the folk medicine to cure rickets.

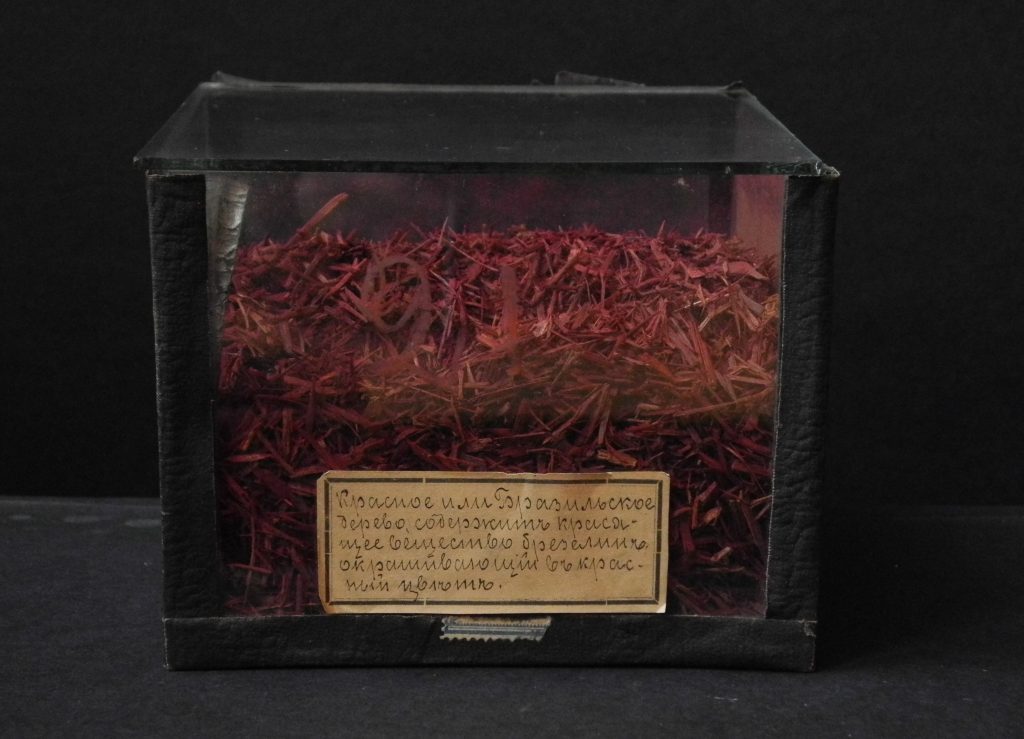

Brazilwood (Lat. Caesalpinia echinata; Guilandina echinata) was discovered by Portuguese scholars on the shores of Saouth America. It contains a dyeing substance called “brazilin”, which is colorless, but becomes yellow as a result of oxidation. After some time it becomes more reddish and turns into good red color called Brazilein after the addition of 5% NaOH (sodium hydroxide).

Brazilwood was actively used in furniture industry and also for violin bows, but now it is listed among the endangered species with the initiative of IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature).

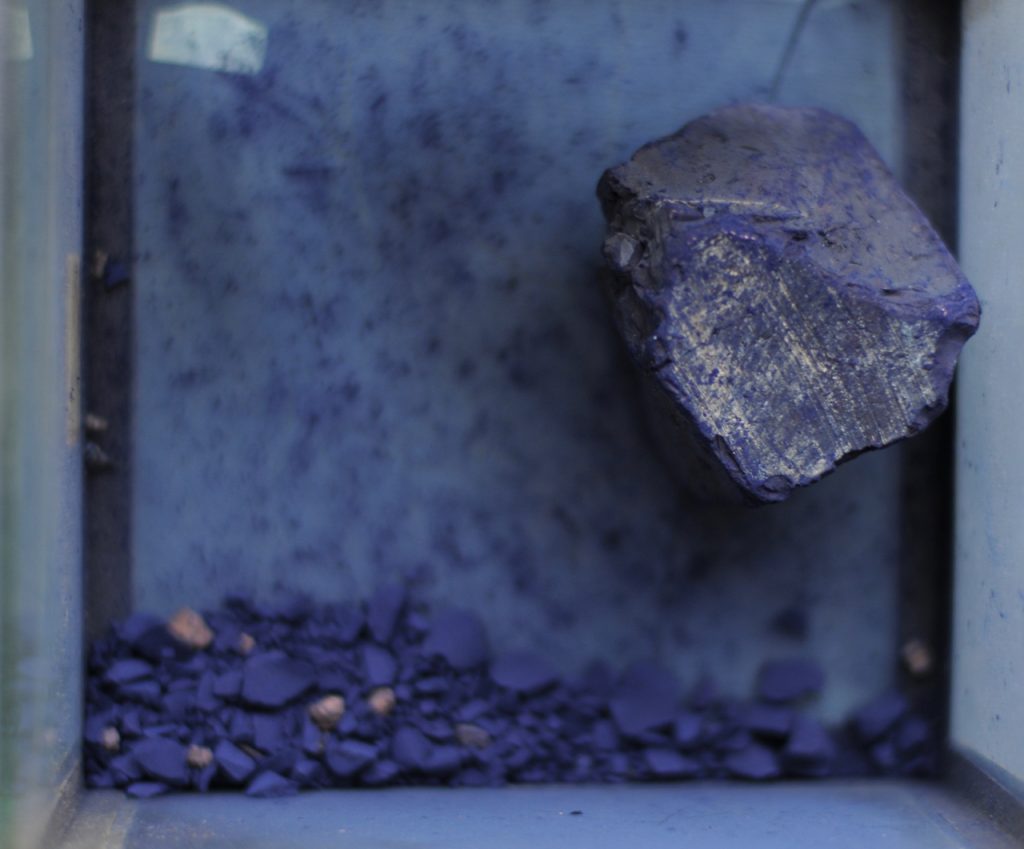

Indigo (Lat. Indigofera tinctoria) originates in India, which is reflected in its name. The plant was not historically cultivated in Georgia and even today it can only be found in Batumi botanical garden. Indigo was very spread on the whole territory of Asia. It was well known in Mesopotamia, Egypt, Greece and Roman Empire. Due to it’s high price indigo was often referred to as blue gold. Historically indigo was imported to Georgia from Persia and traditional Georgian blue tablecloth was usually dyed in it.

Processing indigo is dangerous for human health as it is toxic. There even was a peasant revolt in Bengal in 1859 protesting the cultivation of indigo. Today thousands of tons of synthetic indigo is produced yearly, which is mainly used to dye blue jeans.

One of the distinguished animal dyes from the museum collection is Cochineal (Lat. Dactylopius Coccus; Coccus cacti). Cochineal is an insect, which lives on cacti in the genus of Opuntia and dye carmine is derived from it. Cochineal is mainly spread in mount Ararat surroundings as well as in the Central and North America. It was used as a red dye by Aztec and Maya peoples as early as 2nd century B.C.E. Today it is included in IUCN Red List. Cochineal is also used in homeopathy.

Apart from the natural dyes the museum preserves a collection of above mentioned aniline dyes first discovered by Sir William Henry Perkin in 1856. They spread quickly and replaced natural dyes very soon. Nowadays aniline dyes are very diverse: there are up to 8 000 gradations of them.

One of the well known aniline dye in Georgia is Brilliant Green (Lat. Viridis nitens). We are familiar with it as an antiseptic solution, which is very popular in post Soviet countries while the rest of the world considers it unhealthy and unpractical.

One of the main difficulties of dyeing is color resistance. It is well known that different dyes have different levels of resistance and it is preferable to add mordants while dyeing. The museum preserves various mordants: Wine stone (Potassium bitartrate (cream of tartar) +Potassium tartrate); Cupric sulfate (Lat. Chalcocyanite); Alum (Lat. potassium Alum) and Iron(II) sulfate (Lat. Ferrous sulfate). Additionally, there are above mentioned oak apples and cachou.

Author: Salome Phachuashvili