“Pop-Up: Textiles” was a site-specific exhibition that took place on October 28-29, 2022 at a textile shop in Tbilisi (Queen Tamar Ave. 17) with the support of TBC. This project was yet another result of artistic and research collaboration between Nino Kvrivishvili and Data Chigholashvili, which generally speaking, responds to the history of Georgia’s textile industry by interrelating topics of fabric production, changing places, time, and memory. After the exhibition, the artist and curator talked about their practices and approaches, as well as the importance of textiles in art and anthropology.

Data: Why did you become interested in industrial textiles, and generally in this topic in your artistic practice?

Nino: While studying textile design at the Tbilisi Academy of Arts, I was learning about the technology and history of textile production in Georgia. After industrialization, the textile industry constituted a large part of our country’s economy.

As a textile designer, I was supposed to become a part of this weaving process, but this never happened. There were only nonfunctioning industries and textiles that were rarely available for sale.

The reality was that the textile art of that time was entirely following the traditions of applied arts. For me, this created opposing interests, and I got curious to find more, diversity and contradictions. Exactly since then, I have been interested in the material of closed industries.

You work between anthropology and art, what is textile from an anthropological perspective? Your interest in this topic?

Data: Textile, as a material that is created and designed by people, as well as daily used as clothing, tells us a lot about society and culture. However, we often find a division of some kind, especially in the context of museums and academia, when more attention is paid to traditional, handicraft material than to industrial textiles, which I think is not less important for analyzing contemporary times. A lot of topics concerning our daily life emerge here – the speed of production and living, labor, ethical issues, using or repeating historic textiles and patterns today, rethinking this in contemporary art, etc.

In this case, it is interesting to observe Georgia’s textile industry, which just disappeared, similar to many other industries, and based on this, we can talk about a lot of topics concerning transformation. This finds riveting connections with your works and projects. I would highlight one of the crucial factors here – people’s involvement and role in it. This emerged in our presentations and a talk at the event “They Are There, Sometimes” that took place on March 25, 2022, in the framework of “The Whole Life. Archives & Imaginaries” congress at HKW, Berlin.

What can you say about people’s role in the textile industry? You are working on a project about the biographies of former employees in the industry, which I think, finds a compelling connection with ethnography and anthropology. Why did you decide to work on this?

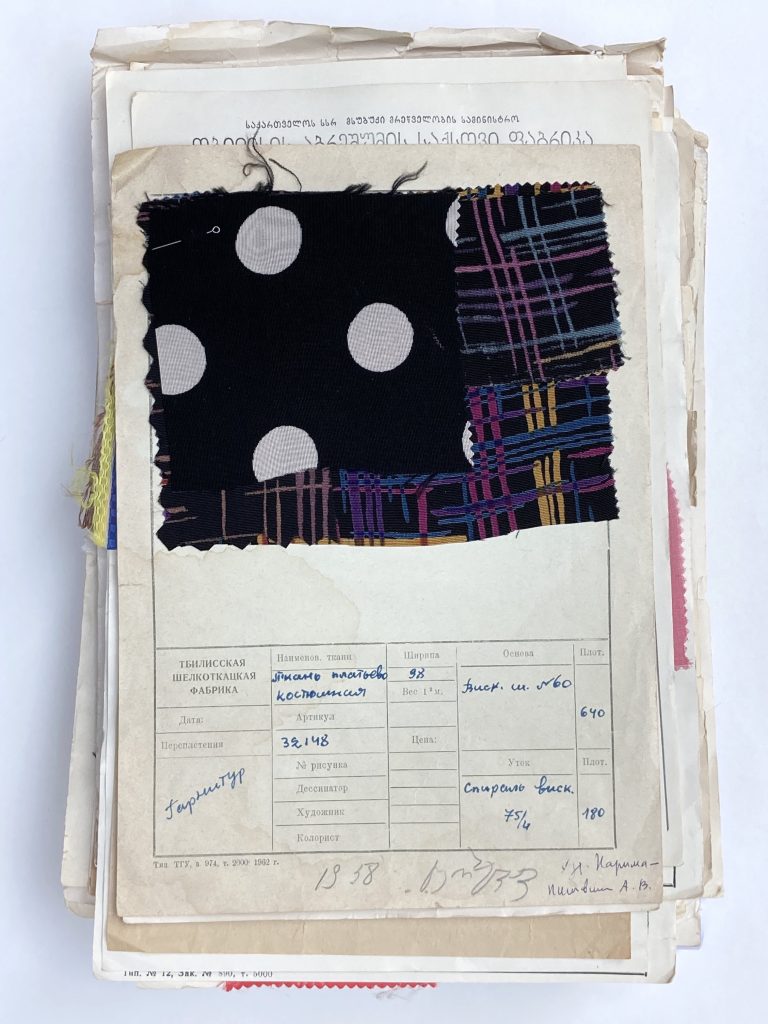

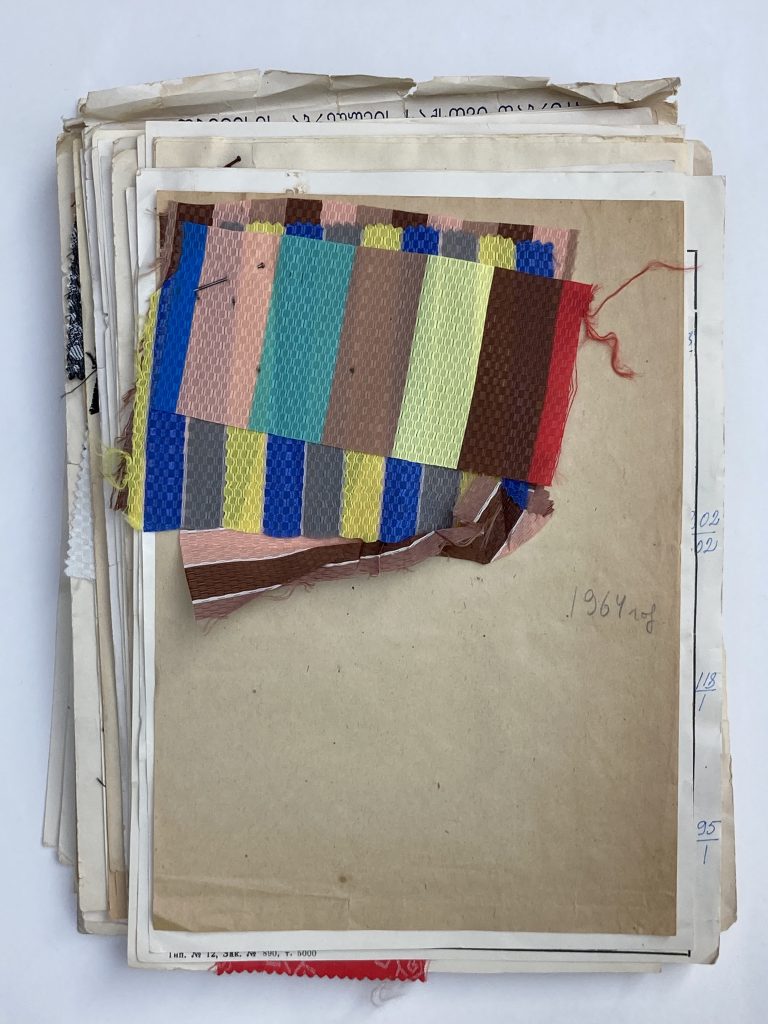

Nino: I started working on the project “Georgian Silk in the 1950s-90s” in the framework of the research residency at the Silk Museum. It took place in 2020, during the pandemic, and concerned the topics of collections and archives, more specifically, the Soviet-time industrial textile samples from the Tbilisi Silk Weaving Factory, which are preserved in the museum’s collection.

Today, nobody is talking about closed industries. Nobody is mentioning the people who were working there. Tbilisi’s silk production, together with other textile industries, was one of the most important in Georgia. Its historic building on today’s M. Kostava Street now has a different function. Many artists, designers, engineers, and so on used to work here. They were creating unique samples until the industry closed down.

I am still interested in their social role, art in everyday life, their tradition of working, and the historical perspective that they lost, distancing them from the dynamics of life. Interested in the life and work of these people, I met with those living in Tbilisi – the main engineer Elene Sepiashvili, and artists, Natela Taktakishvili and Mtvarisa Markozia. Their main work in production stopped when the industry closed down.

Historically, women had an important mission in the industry. A lot of men were drafted into the war, and women were the main workforce.

What was interesting for you in the project concerning the research of industrial textiles?

Data: The Silk Museum’s collection contains a lot of samples from the factory, which are also very interesting in the way they are presented – there used to be special forms, more or less on A4-sized papers, where information should have been completed about the artist, designer, etc., a lot of details should have been provided, and also, the textile sample was supposed to be inserted. This information is partially provided, sometimes we only find the initials of first names, and gradually this form of presentation was changing as well. There are samples that are just pinned on empty papers, this form seems to be entirely disappearing in time, as if it was losing itself and predicting that all of this was going to vanish.

Organizing this for research was one of the interesting topics here. We decided to sort them according to the authors. There were those where the author’s name was not provided and I think this turned out to be the biggest group in the end. If I remember correctly, in the beginning, for this I noted down “without the author” and then I changed this because, in principle, none of them are without the author, just they were unknown to us.

First and foremost, I was interested in organizing and looking at how the material can be sorted, so that you can start researching, and based on that, what should be analyzed? What additional material should be collected? To look at it in process and think about how to work on this in the future. In a way, you and I continued collaborating on some of the topics present here.

Nino: How can this be organized and presented?

Data: Material in the collections of museums is just one side of it. The textile industry was huge, it was not just silk, you have also worked a lot on this. There were a lot of factories and productions throughout Georgia, we all know that it was happening on a massive scale, they were working on various textiles. I think it is already very important to add personal stories, personal collections and narratives. Generally, it is typical of big industries that the personal aspect disappears, and this was especially so in the Soviet industry, unless they wanted to use the stories of successful employees for propaganda. Therefore, today we should bring more anthropological meaning to it, and add corresponding stories. I think that working precisely in this direction would be very important and interesting because perhaps, we are running out of time as well. Otherwise, a big part of history will be lost. That’s why I think that your approach, for instance, collecting biographies, your text about the factory, and generally all you do, is very timely, and at the same time, very anthropological as well. Maybe this is not necessarily your starting point, but I believe that in your artistic practice, to a certain degree, you are also conducting ethnographic and anthropological work regarding the topic.

In relation to this, on the one hand, we see collecting and working on the stories of others, on the other hand, rethinking personal experience. Therefore, I am interested to know to what extent is self-reflection important to you. The story of your grandmother has a significant place in your works. Why did you decide to transform your and your family’s history into artworks?

Nino: When I am talking about the industry, the story of my grandmother, Raisa Zatyukova is directly connected with what I do today. My grandmother used to work at the cotton mill in the city of Gori and she is a part of the same story that I mentioned regarding women. She started working at the mill in the 1950s, during the industrialization, after arriving here with textile masters from the city of Ivanovo (Russia). After many years of working there, in the 1990s, when the cotton mill of Gori ceased to exist, a lot of people lost their workplace. This was the time when people were searching for parallel jobs in order to survive.

This is when many textile masters decided to leave Georgia and go to their home country. My grandmother stayed in Georgia and still lives here. She talks a lot about the industry, it could be said that she prologs the existence of this history.

This information appeared in my works as well. The textiles, which I have been creating myself for many years now, often have symbols and signs connected with the textiles from the time of industrialization and frequently refer to lost moments. The stories of everyday objects appear with textiles, creating a certain image of these people, time, and history.

“Searching for Traces” is a vitrine of everyday objects that tells the story of people who left Gori in the 90s and went back to their home country. The war significantly damaged the lives of these people, and Georgia was not their personal choice. But after living in Georgia for many years, they had to leave their homes, and they left their belongings with my grandmother, hoping that one day they would come back.

The work “Do You Want to Live in Paradise?” continues the same topic. It poses an ambiguous question regarding those people, who still only reminisce about the recent past. Here everyday objects are presented with simple cardboard boxes, as well as on solid concrete and wooden pedestals, which is in a way a metaphor for building a house. I am interested in seeing the social role of working people, their everyday lives, and not being nostalgic, or making social criticism about them.

In Zürich, I created a series of silk textiles called “Beyond.” The abstract shapes, which are transferred on silk, narrate the stories of women who were involved in the silk industry of Zürich. In a way, the textiles are curtains, which in scale are similar to the windows of the industry’s settlement, and the actual lives of women are concealed beyond them.

How do you see the city-textile connection? What could be an anthropological study of this topic?

Data: I work on many topics concerning urban transformation, wherein the city-textile connection emerged more actively in previous years. I think that in this case, if we are talking specifically about the connection of Tbilisi and textiles, here we already have to pay more attention to the past. As the textile industry does not exist anymore and very little remains, we are already looking at the topic in the context of a postindustrial city. Of course, the textile industry was very big, but it was just one part of an even larger industrial system, which tells us what happened in Tbilisi, and generally in Georgia during the previous three decades. However, this narration requires collecting people’s stories, their experiences, analyzing them in relation to today’s situation, and presenting accordingly. We have to look at how Tbilisi transformed, and as a matter of fact, how it has been transforming in the postindustrial context. I think this was very interesting in our research and yet another collaboration, the “Pop-Up: Textiles” project. Within the concept, we inverted this fast, “pop-up” speed of the 21st century, and made the exhibition in the textile shop that has been there for several decades. Our collaboration, as well as talking with visitors based on your works and installation at an exhibition of such a format, altogether was a very impressive experience for me. I think we remembered and learned a lot about the history of industrial textiles in the city.

This working process, making the exhibition at the textile shop, and interacting with visitors, what kind of experience was this for you?

Nino: I was always interested in the textile shop, in its role and aesthetics in the urban everyday. The exhibition “Soviet Rainbow: From Textile Shop to Museum” took place in 2016 at the Silk Museum, and it also dealt with the topic of the textile shop in Tbilisi. One of the installations, freestanding concrete and wooden sculptures with old silk fabrics created a shop atmosphere.

In 2020, together with curator Tara McDowell, and in collaboration with the “Incidents (of Travel)” project by Latitudes, I made a tour in Tbilisi. I wanted to show the curator the places in the city, which I love the most and that appear in my daily activities. I started the tour at the former building of silk production, then a former textile shop on Rustaveli Avenue, and later one of the stops was at this functioning textile shop.

Everybody knows about Alexandre Utmazyan’s textile shop, which is located on Queen Tamar Avenue, on the left bank of the Mtkvari River in Tbilisi. The old sign that says “textiles” is still there. This textile shop is a rare commercial spot in the city, which to this day retains its initial image and function.

For me, the exhibition “Pop-Up: Textiles” was a temporary show and in a way, a cycle as well – a constant repetition of what I do. For two days, I was observing events in a long-term, prolonged time. Together with the old silk textile that was produced in Georgia, I presented paintings on the theme of lost industry. As if, these paintings appeared in another time for me, and it was good to look at them from a distance.

Data, I have worked with you on different projects. I should mention our dialogue at HKW in 2022, where we talked about archives, the industry’s context, people’s roles, etc. Your interests and experience, considering your educational background in anthropology, were reciprocally interesting when working on the “Pop-Up” exhibition. As we know, art is often connected with places and contexts where people live and work. I think we both represent this environment, but the aim of our exhibition was not to directly represent the past. Being inside the shop, during its working hours for two days, and meeting people, showed us this history from a further distance, which I think is very good in a long-term perspective.

Pop-Up: Textiles

28-29.10.2022 / 10:00 – 18:00

Textile shop, Queen Tamar Ave. 17, Tbilisi

Artist: Nino Kvrivishvili

Curator: Data Chigholashvili

The project was supported by TBC

VR documentation of the exhibition can be seen on the webpage: datach.me