I worked on the project Pirimze for several years. I researched this building from different angles and met a lot of people who worked there. As a result, I created various works – installations, a book, and a documentary film.

Pirimze was built in 1972 as a place combining different types of individual services. In the magazine Pirimze (1981, issue 3), we find the following description of the building:

“For a long time, the establishment of household goods and services “Pirimze” has been popular among the city dwellers, as well as the guests of the capital city.

All the main types of services are provided here.

On the first floor, which is always crowded, qualified craftsmen will fix: a piece of electrical equipment (an electric shaver, a coffee grinder, a meat mincer) or a clock, a domestic and an imported umbrella, haberdashery, they will bring chandeliers and porcelain products to their original state… You can get the texts engraved on objects, duplicate apartment keys, fix children’s toys, buy a national drinking vessel – Kantsi. Dry cleaning is also available here.

Music lovers can use the audio library of the recording studio on the second floor, fix a cassette player, a radiogram. Also, here you will get the services of experienced photographers who will develop films.

If you visit the third floor, international and all-union prize-winning hairdressers and designers, qualified cosmetologists, manicure and pedicure technicians will offer you their services.

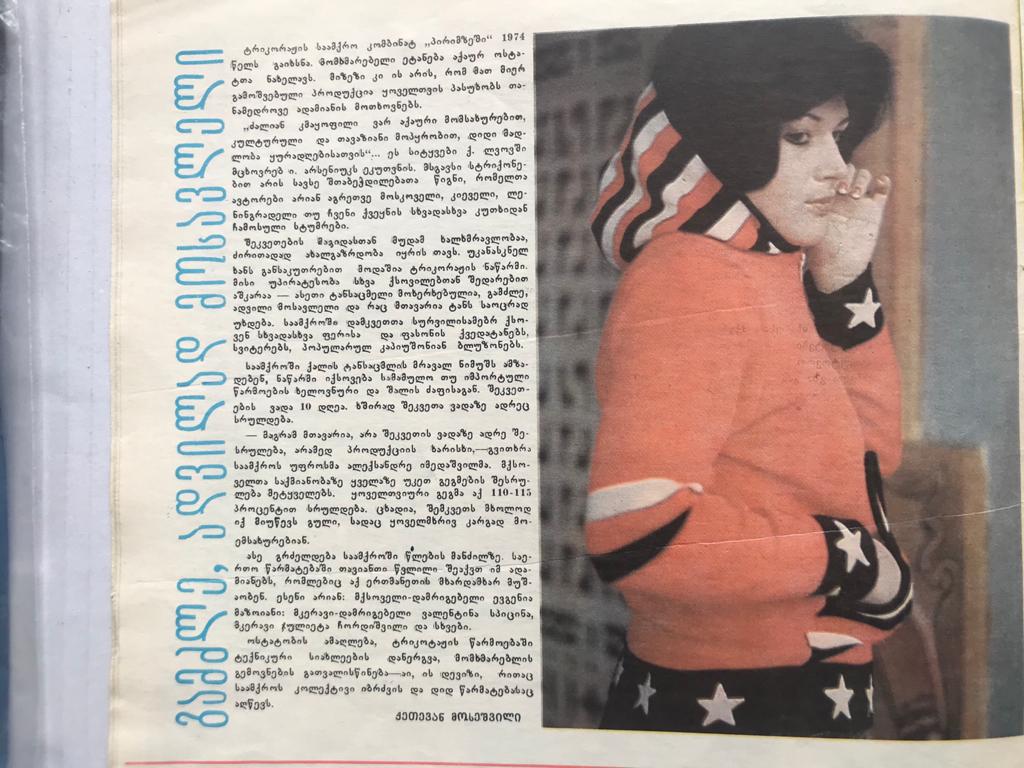

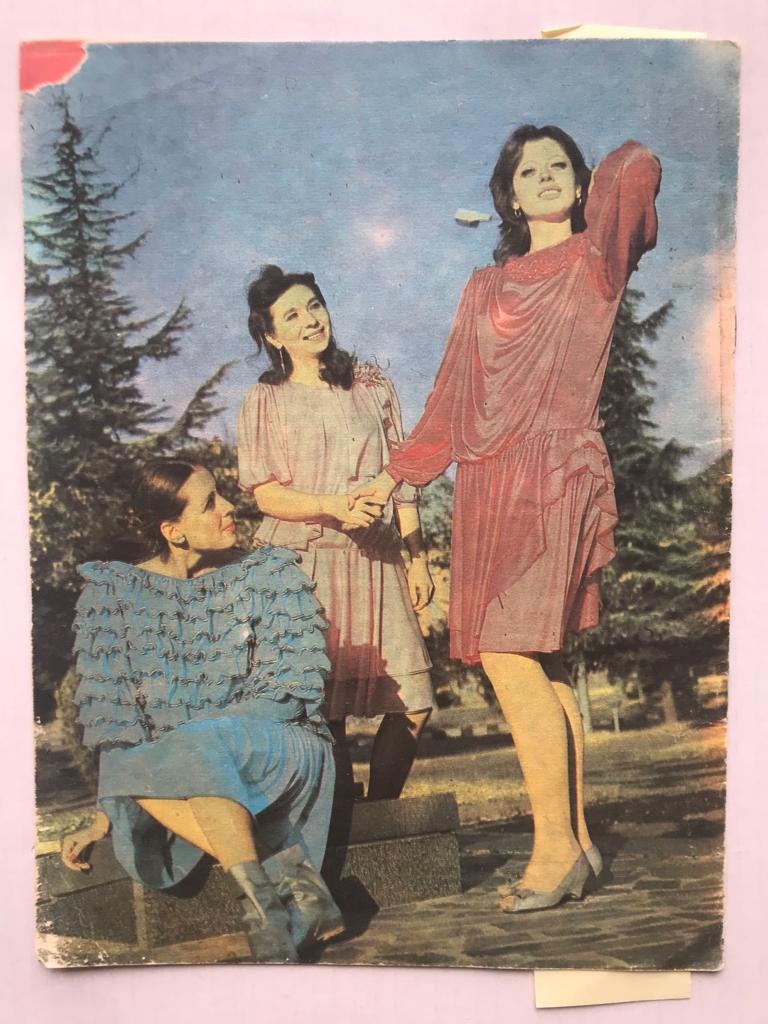

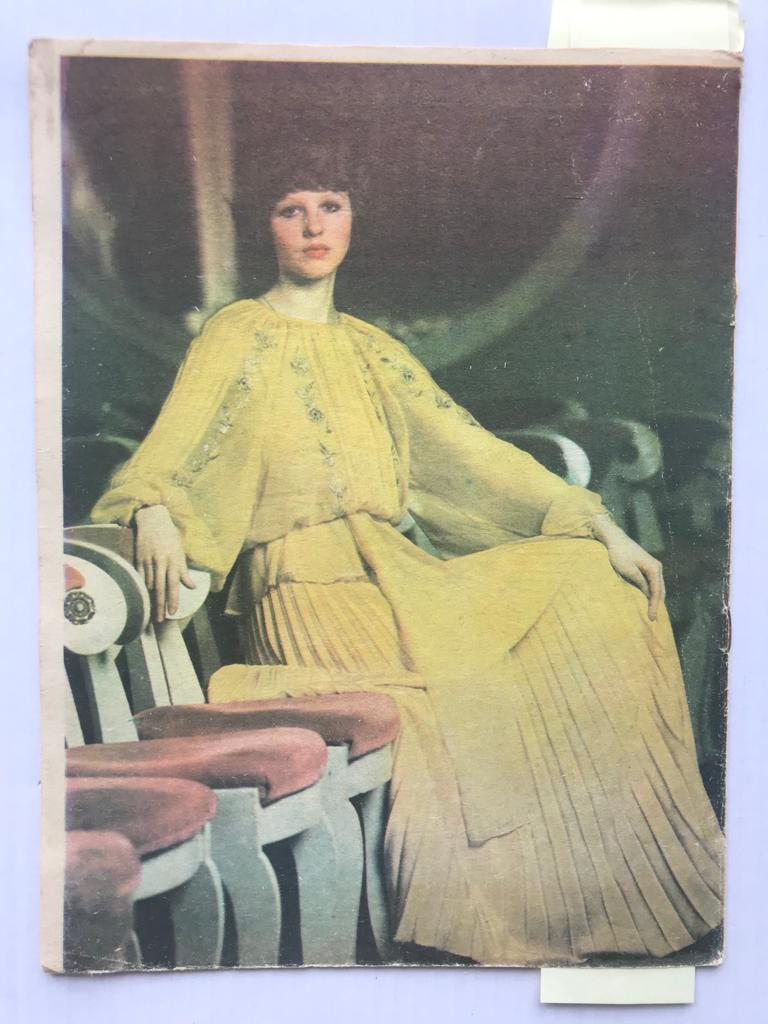

You can buy fashionable stockinette clothing on the same floor.

Beautiful, fashionable shoes can be bought on the fourth floor.

The second and the fifth floors are used for custom-tailoring, where you will get the services of the highest-ranking tailors.

Use the service of the union “Pirimze”! This will save you time, and help you deal with many pressing problems.”

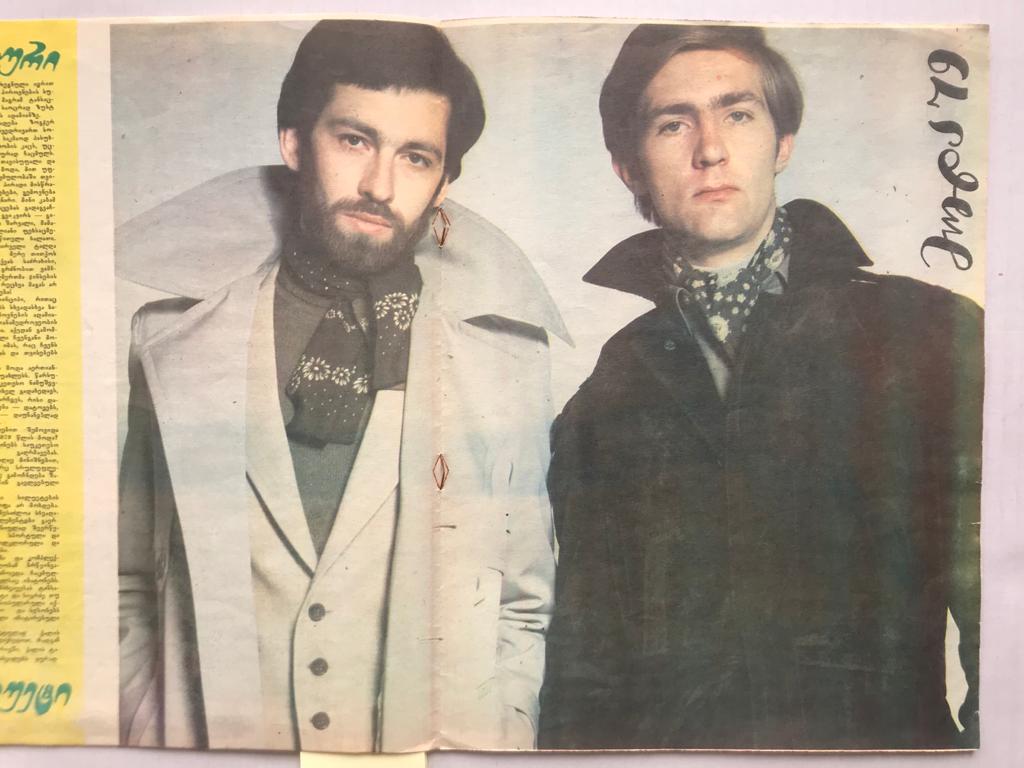

In Soviet reality, Pirimze was a small model of capitalism. Its workers knew the value of money, the market rules, and due to this, they had “individualistic and proprietary characteristics.” It seemed that after the collapse of Soviet rule, in the new reality these craftsmen should have been able to prosper and reach new heights of money-making. However, this generation, and perhaps especially the men of this generation, still found it difficult to move from the Soviet system to “contemporary reality.”

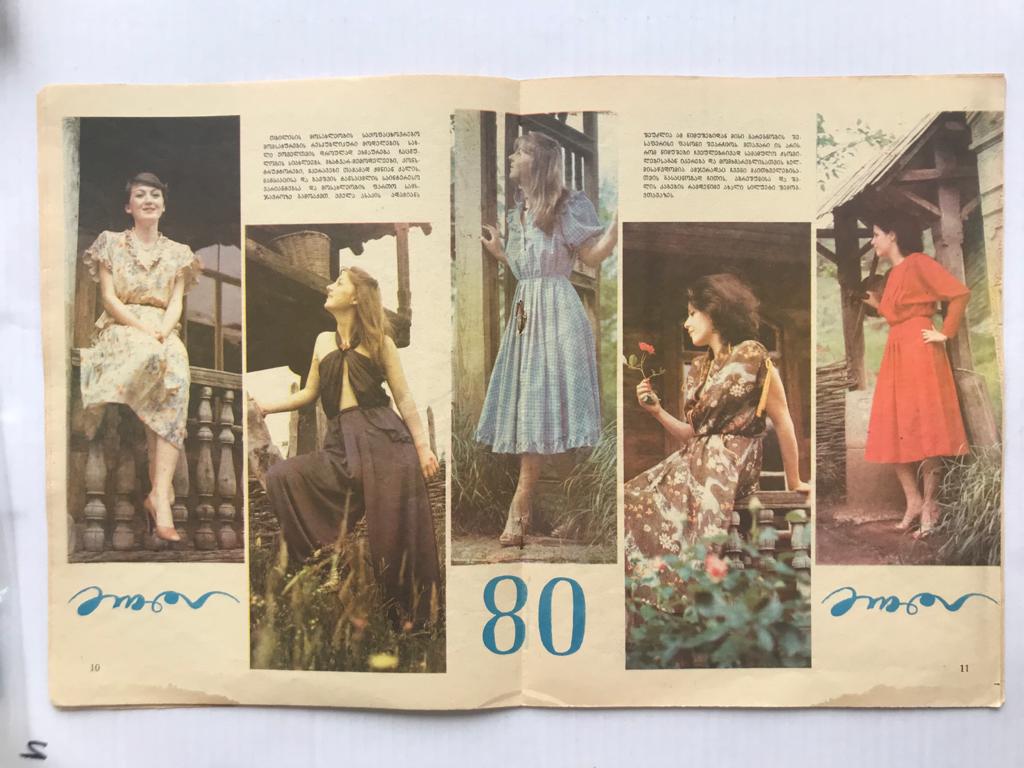

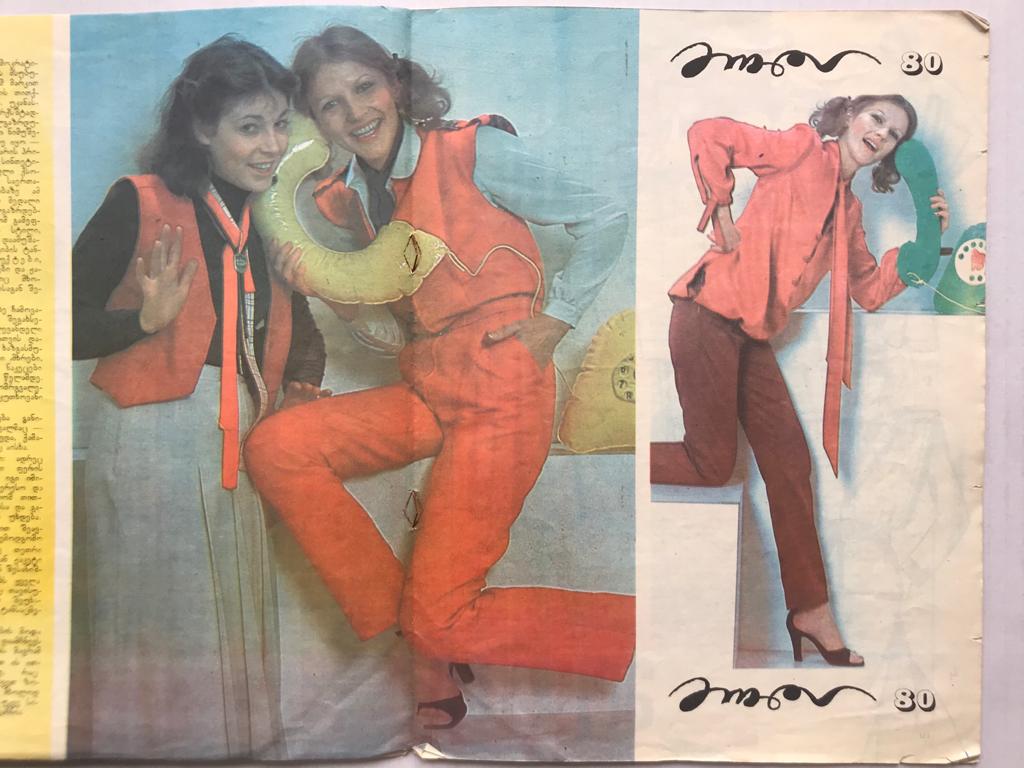

As I was preparing a lecture for the Silk Museum, I took the magazines of Pirimze. I wanted to look at the building through textiles and I started to explore the fashion of that time.

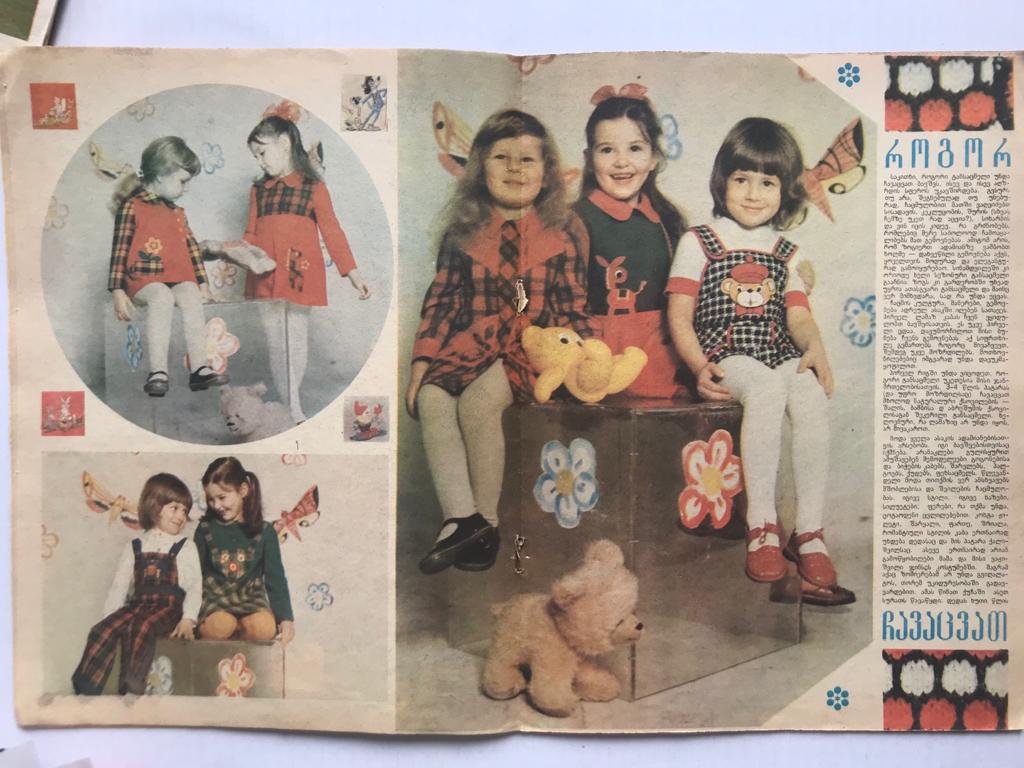

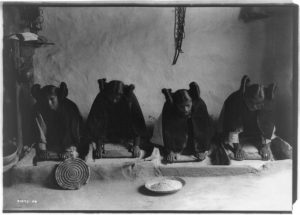

While I was looking at the fashion photographs from the 70s and the 80s, I remembered my grandmother, my father’s mother who was a seamstress. Whenever I would visit her in my childhood, I would always encounter the same situation: various women were gathered in her small sewing workshop. They were trying on dresses and discussing different topics. When I think about it today, I would gladly listen to these talks again. It’s interesting if I would be able to see this room through the feminist perspective, as a temporary escape from the patriarchal reality – unfiltered discussion of topics that interested them, and without men’s gaze, freely showing their bodies among other women at fitting.

Perhaps, the magazines of Pirimze should have included clothing relevant to these women’s taste. However, the women in this room were not going through the issues of Pirimze. Instead, they were interested in foreign clothes. There were two thick German magazines – Otto and Neckermann, the pages of which had tattered from looking through them. My grandmother’s customers wanted clothes similar to what they saw in these journals.

Pirimze was created exactly with the purpose of terminating individual booths and such tailor shops that were operating inside houses. In the magazine Pirimze (1975, issue 6) we read the following text provided in the “Soviet spirit”:

“Booths, Booths…

Booths remain as a #1 problem.

As a rule, opening establishments of household goods and services, industrial complexes, ateliers, and salons should be followed by reducing and abolishing booths with 1-2 persons in them. But…

We find booths in yards, streets, salons, and imagine, inside industrial complexes as well.

What do we have against booths? Why do we try to terminate them?

A craftsman, who has individually settled down, becomes restricted, involuntarily separates from the collective, its good influence, and becomes self-satisfied, self-assured.

Craftsmen, who have isolated themselves from the collective, get individualistic, proprietary characteristics. They try their best to keep independence and fully cling to unstable, hollow, disorderly booths.

Using machinery, introducing technological innovation, and properly organizing labor are not possible in booths. Like other fields of the national economy, the development of household services is based on scientific and technical achievements.

In this case, it is impossible to find something in the middle. There is the only right way – abolishing old, obsolete relics, which are absolutely inappropriate to our life, and change over the “booth services” to contemporary reality.”

In 1995, the status of Pirimze changed from state ownership to shareholding enterprise, and the craftsmen became shareholders. In 2003, the enterprise declared bankruptcy, and a part of the building was sold at an auction. In 2007, all the craftsmen were dismissed and the building’s reconstruction began. I started to work on the project in 2011. At this time, the building of Pirimze was already transformed into Pirimze Plaza, an empty and characterless “class A” business center.

As Pirimze did not exist anymore, all I could do was to go to scattered, small “disorderly booths” that had appeared around the building, and search for people who would remember something about Pirimze. I occupied a table at one of these workshops and started to talk with the craftsmen. I was asking them to remember their working places, what people specialized in, and which spots they worked at inside the building. This is how I met Koki Beridze. He had a lot of information about the fight for Pirimze and gladly shared everything with me. Once we became close friends, I asked him how the craftsmen would operate Pirimze in today’s reality, had they not lost their shares and kept the building. As I was expecting something idealistic in response, he told me that a lot of things could have been done here, even a center for limousine service…

If I had an opportunity to appear in my grandmother’s sewing workshop now, probably, I would not have been able to find something feminist in those discussions.

The film can be seen on this link (password: pirimzeforever)

Author: Sophia Tabatadze

The text is an adapted version of a lecture made in the framework of the online program “What Is Textile Telling Us?”. The program is implemented by the State Silk Museum through a grant from CEC ArtsLink’s Art Prospect program.